Talk:Mahābhārata

By Swami Harshananda

Prologue[edit]

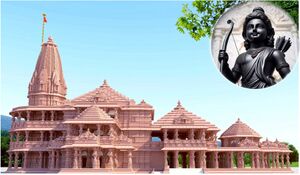

Rāmāyana and Mahābhārata are the two great epics of India. It has captivated the hearts of its people for several millennia. No aspect of Indian culture has escaped the stamp of their influence in any field of life mentioned below:

- Sanskrit Literature

- Vernacular Literature

- Arts

- Crafts

- Painting

- Music

- Dance

- Drama

- Temple Motifs

The simple village folks get sentimental while listening to the ballads on the banishment of Sitā. Even the highly skilled artisans working on the temple motifs depicting the Kurukṣetra war get emotional while sculpturing it. People hugely respond to a dynamic and perennial culture of these epics. Religious tradition has always considered these two epics as itihāsa, or history. Modern scholars have largely conceded that the core of the epics could have had historical basis.

Date of Mahābhārata[edit]

All the reputed scholars from the world have battled for years to fix the date of the Mahābhārata war. This war is also known as the Kurukṣetra war. Incidentally this would also fix the date of its heroes and their historicity. If the meticulously preserved oral traditions based on their notion of time as the yuga-system are to be relied upon, the great war should have taken place during 3139 A. C. Writings of Megasthanes (312 B. C.) as internal astronomical evidence corroborate this date. However, modern historians have assailed this theory. They are inclined to accept a much later date that is either 1424 B. C. or 950 B. C.

Author of Mahābhārata[edit]

Traditional lore ascribes the authorship of this epic to the great sage Vedavyāsa. He was also known as Kṛṣṇa Dvaipāyana. He was a contemporary of the grandsire Bhīṣma. He had a firsthand knowledge of most of the events described in the epic. However, research scholars feel that the original work called Jaya, written by Vyāsa to commemorate the victory (jaya = victory) of the Pāṇḍava princes over the wicked Kauravas might have been a much smaller work comprising about 8,800 verses.

Work written by Vyāsa was subsequently revised and enlarged into Bhārata. It is a work of 24,000 verses by Vaiśampāyana. He was a disciple of Vyāsa and recited during the Sarpayāga[1] of Janamejaya, the great-grandson of the Pāṇḍava hero Arjuna.

The final edition that has come down to us is the work of Suta Ugraśravas, son of Lomaharṣaṇa. His name is also spelt as Romaharṣaṇa. It was recited at the Sattrayāga[2] of the sage Śaunaka in the Naimiṣa forest. This upgraded version was termed as Mahābhārata. It was named this due to the immense size (mahā = great) and its dealing with the story of the people of the race descended from the ancient emperor Bharata culminating in the war.

This edition is reputed to be ‘Śatasāhasrī Samhitā’ as it is collection of 100,000 verses, though the extant text is less. The round figure is obviously an approximation. Some scholars have tried to establish that the epic has evolved over a period of eight centuries from 400 A. C. to A.D. 400 to its present proportions. At the present stage of the research, it has not been possible to clinch the issue and hence chronological questions continue to remain open to discussions.

Recensions and Commentaries[edit]

Different regions of India have preserved different recensions of the text of this epic. These have been broadly classified as the Northern and the Southern recensions. Scholars opine that the Southern recension is the longer of the two. It is more impressive because of its precision, schematization and practical outlook.

One of the standard editions published contains 95,826 ślokas or verses in 18 ‘parvans’ or books. These books further have 107 sub-parvans and 2,111 chapters in total. It also includes the appendix Harivanśa. It gives an idea of the immensity of this epic poem which is eight times as big as Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey put together.

Since the text contains quite a few riddles known as kutaślokas, vast portions of didactic material and several commentators have tried their skills on it. The gloss of Nilakaṇtha[3] is more well-known. It is also among the material which is widely referred to.

Analysis of the Contents[edit]

The contents of the eighteen major books may be briefly summarized as follows.

Ādiparva[edit]

It is the first book. It is fairly long and deals with several ancient episodes like:

- Episodes connected with Śukrācārya, the preceptor of the asuras

- Śukrācārya's intractable daughter Devayānī

- About Yayāti, a prominent king of the lunar dynasty

- Famous romance of Śakuntalā and the king Duṣyanta

- Story of the ancestors of the Pāṇḍavas and the Kauravas like antanu, Bhīṣma, Vicitravīrya, Dhṛtarāṣṭra and Pāṇḍu

- Birth and education of Pāṇḍavas and Kauravas

- Early rivalries between Pāṇḍavas and Kauravas

- Marriage of Draupadī, the Pāñcāla princess, to the Pāṇḍavas

- Arjuna’s pilgrimage and marriage with Subhadrā, sister of Srī Kṛṣṇa

Sabhāparva[edit]

It is the second book. It deals mainly with the following:

- Performance of the Rājasuya sacrifice by Yudhiṣṭhira

- Eldest of the Pāṇḍava princes

- Game of dice maneuvered by the wily Duryodhana, the eldest of the Kauravas

- Tragic consequences for the Pāṇḍavas

Araṇyaparva[edit]

It is also called as Vanaparva and sometimes as Āranyakaparva. It is the third book that covers the following:

- Story of the Pāṇḍavas in exile at the Kāmyaka forest

- Stories of Nala and Damayanti

- Stories of Sāvitri and Satyavān

- Stories of sages like Rṣyaśṛṅga, Agastya and Mārkaṇḍeya,

- Stories of the kings like Bhagīratha and Sibi

- The famous quiz Yaksapraśna

Virātaparva[edit]

Virātaparva is one of the smaller books dealing mainly with the following:

- Stay of the Pāṇḍavas incognito in the kingdom of Virāṭa

- Slaying of the villain Kīcaka

- Battle for rescuing the cattle of the king Virāṭa which had been captured by the Kauravas to force the Pāṇḍavas to come out of their hiding

- Wedding of the Virāta princess Uttarā with Abhimanyu, Arjuna’s son

Udyogaparva[edit]

It is also a short book which deals with the follwing:

- Peace parleys and preparations for the war curiously going together.

- Touching scene of Kuntī, the mother of the Pāṇḍavas

- Disclosing to Karṇa the secret of his birth in her womb

- Statesmanship of Śrī Kṛṣṇa who makes a last minute bid for peace

- Famous discourse of the sage Sanat-sujāta to the blind king Dhṛtarāṣṭra, well-known as the Sanatsujātīya, which is full of philosophical truths

Bhiṣmaparva[edit]

It contains the following topics:

- Crown-gem of the epic, the Bhagavadgitā

- Detailed descriptions of the first ten days of the war containing the superhuman exploits of the grandsire Bhīṣma

- Him being mortally wounded by Arjuna

Since Bhiṣma had the unique boon of dying at will, he preferred to lie down on the bed of arrows and postpone his demise till the beginning of Uttarāyaṇa or the northern solstice.

Droṇaparva[edit]

It is the seventh book depicting the following:

- Heroic exploits of Droṇa, the preceptor, culminating in his death through stratagem

- Account of the brilliant achievements of the boy-hero Abhimanyu on the battlefield and his tragic death

Karṇaparva[edit]

It is the eighth book which details the following:

- Gory death of the evil genius Duśśāsana, the second of the Kaurava brothers, at the hands of the colossal Bhīma

- Fall of Karṇa himself at the hands of Arjuna after a bitter fight

Śalyaparva[edit]

It is the ninth book which describes the following:

- Final encounter between Bhima and Duryodhana on the last day of the war

- Duryodhana succumbing to the mortal blow received during the duel

Sauptikaparva[edit]

It delineates the following:

- Gruesome massacre of the Pāṇḍava army and its allies in the night during the sleep by Aśvatthāman, Droṇa’s vengeful son

Striparva[edit]

It describes the pitiful lamentations of the women and the widows of the dead warriors graphically.

Śāntiparva and Ānuśāsanikaparva[edit]

They are the twelfth and the thirteenth books. They contain the following:

- Wonderful discourses on all aspects of dharma by the patriarch Bhīṣma at the request of Yudhiṣṭhira

- Bhīṣma’s demise

- Yudhiṣṭhira’s coronation

- Viṣṇu sahasranāma

- Śivasahasranāma

- Anugitā, a subsidiary discourse by Śrī Kṛṣṇa to Arjuna

Āśvamedhikaparva[edit]

It is the fourteenth book which describes the following:

- Departure of Śrī Kṛṣṇa for Dvārakā

- Horse-sacrifice, Aśvamedha, performed by Yudhiṣthira

- Humiliation of Yudhiṣthira by a talking weasel that describes the supreme sacrifice of a brāhmaṇa family

Āśramavāsikaparva[edit]

It describes the following:

- Departure of the old Dhṛtarāṣṭra to the forest along with Gāndhārī, his spouse, and Kuntī

- Their subsequent death in a forest fire

Mausalaparva[edit]

It depicts the following:

- Account of the mutual destruction of the Yādava heroes

- Death of Śrī Kṛṣṇa by a hunter

Mahāprasthānika and Svargārohana Parvas[edit]

These are the last two days which gives an account of the following:

- Account of the final journey of the Pāṇḍavas

- Their death on the way

- Yudhiṣthira alone reaching heaven

Characters[edit]

The Mahābhārata depicts a veritable array of human characters from the sublime to the ridiculous. No type of human emotions, no deed of valor, generosity, sacrifice or meanness is missed here. Nor is there any artificiality in these portrayals. A brief delineation of some of the more important characters may now be attempted here.

Śrī Kṛṣṇa[edit]

Śrī Kṛṣṇa is undoubtedly the most brilliant and picturesque personality projected by the epic. He appears in the epic rather suddenly at the time of Draupadi’s svayamvara,[4] and continues to saunter the scenes right up to the end. All his energies are channelized only in the following directions:

- Protection of the right and the good

- Punishment or destruction of the wicked

His remarkable prowess, matched only by the bewitching beauty of his perfect form, sage counsels, superb stratagems and immensely superior statesmanship, captivate our heart. There is absolutely no doubt that the epic projects him as God Himself who has come down to save mankind. He himself admits this in the Bhagavadgitā.

Bhīṣma[edit]

Bhīṣma, the great grandfather of the pāndavas and the kauravās, is another towering personality that awes and inspires us throughout the epic. He has proved his supremacy in the sacrifice of abdicating his right to the throne, the vow of celibacy and the matchless heroism on the battlefield.

Śrī Kṛṣṇa recognized his encyclopedic knowledge and wisdom and got it preserved for the posterity by prodding him through Yudhiṣthira to unfold it. The Śānti and the Ānuśāsanika Parvas are practically the repositories of his teachings.

Yudhiṣthira[edit]

Yudhiṣthira is the eldest of the Pāṇḍavas. He is perhaps the most dominant character of the epic, next to Śrī Kṛṣṇa. He was not only a great hero on the battlefield, true to his name (yudhi = in battle, sthira = one who is steady), but a veritable incarnation of dharma or righteousness, a rare combination indeed.

Hence, he is often addressed as Dharmarāja which means ‘the monarch of righteousness’ also. He would never swerve from the path of ethical uprightness in any critical circumstances. His thinking about dharma was always crystal clear. The Yaksapraśna-episode is replete with the gems of his wisdom.

Bhīma & Arjun[edit]

The epic pictures Bhīma, the colossus and Arjuna, the warrior, in more human terms. Bhīma was the personification of down-to-earth common sense. Arjuna is more idealistic and dreamy. However, both were extraordinarily devoted to Śri Krsna. Both of them were implicitly obedient to Yudhiṣthira.

Droṇa[edit]

Droṇa was the preceptor-warrior. He was forced to take to the military profession in spite of being a brāhmaṇa. He appears to be a shade darker than Bhīṣma. Notwithstanding his learning and austerity, he exhibited a streak of vengeful nature.

Vidura[edit]

Vidura was the son of the maid-servant. He is another personality who strikes us not only by his sagacity but also by his intense devotion to Śrī Kṛṣṇa. He had no doubts about the divinity of Śrī Kṛṣṇa. He was a living example to show that it is not birth or caste that makes for greatness but intrinsic character. His discourse to Dhṛtarāṣṭra in the Udyogaparva is now well-known as Viduraniti.

Duryodhana[edit]

Duryodhana was the eldest of the Kauravas. He is the chief villain of the epic. His greed and jealousy overshadowed whatever heroism or virtues he had resulting in the total destruction of the two races and untold misery to the millions.

Karṇa[edit]

If the word ‘tragedy’ needs any illustration, one should exemplify the Karṇa. He was the victim of circumstances. His story can never be read with the eyes dry or the heart unmoved. He was supremely noble and generous in every inch of his personality. He is perhaps the ultimate example for friendship, loyalty and generosity.

Dhṛtarāṣṭra[edit]

Dhṛtarāṣṭra was the blind and vacillating king. He was blind not only physically but also in wisdom. His inordinate infatuation for his children, the Kauravas, prevented him from exercising his authority to uphold dharma.

Draupadī[edit]

Among the women characters, Draupadī, the Pāñcāla princess and the queen of the Pāṇḍavas has played an inevitable role in the epic. She was endowed with striking beauty. She even had a sharp intellect and a sharper tongue which she could wield effectively. She remained absolutely faithful to her husbands. By her supreme sacrifices, she has set an example of wifely virtues.

Kuntī[edit]

Kuntī was the mother of the Pāṇḍavas. She impresses us as a helpless but noble princess. The fortitude with which she silently bore all her misfortunes and miseries is unparalleled.

Gāndhārī[edit]

Gāndhārī made the utmost sacrifice of denying herself the pleasures of eyesight because Dhṛtarāṣṭra, her husband, was born blind. She is a paragon of the ideal wife. Unlike her husband, she was bold enough to admonish her son Duryodhana for his wicked behavior and warn him of its dire consequences. She was ever devoted to dharma.

Veritable Encyclopaedia of Dharma[edit]

The Mahābhārata is also known as the Pañcama Veda, ‘the fifth Veda’. It is a veritable encyclopedia of religion and culture. The claim of the Suta Ugraśravas is no exaggeration. He states that,

‘Anything anywhere is an echo of what is here’ and ‘what is not here is nowhere’

Dharma has four prime aspects. They are:

- Rāja-dharma - statecraft

- Āpad-dharma - conduct permissible during dire calamities

- Dāna- dharma - liberality

- Mokṣa-dharma - conduct pertaining to emancipation

All the aspects of dharma and life have been covered in Mahābhārata. In fact, the very purpose of the Mahābhārata is to expound dharma in all its ramifications. The celebrated Bhagavadgitā, the less known Anugītā, and two well-known hymns Viṣṇu-sahasranāma and Śivasahasranāma, have been sources of inspiration to philosophers and votaries of religious pursuits over the millennia.

The Viṣṇu sect and the reconciliation of the various warring faiths also find an appropriate place. Along with the growth of rigidity of the caste system, honest attempts at extolling human excellence and treating it as the real basis of brāhmaṇahood are also conspicuous. In spite of the misogynists of the age, women did find a place of honor during the epic period.

Mahābhārata Outside India[edit]

There is enough evidence to admit that the Mahābhārata had migrated outside India also especially to the South-East Asian countries. Incidents from this epic have been portrayed in stone relief in the Angkor Wat and Angkor Thom of Kampuchia.

Epilogue[edit]

Whether the Mahābhārata was the composition of a single poet or the compilation of several editors, whether the great war was fought in 3100 B.C. or 1400 A. C. or 950 B.C., whether it was a family feud or a ferocious war, it is verily the biggest classic ever scripture composed by a man. It will retain its relevance as long as the sun and the moon shine or the stars twinkle. It is the mirrors of the eternal drama for human existence.

References[edit]

- The Concise Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Swami Harshananda, Ram Krishna Math, Bangalore