Talk:Transcending Karm through mokṣa:Karm Yog and Karm:Destruction of Kriyamāna Karm by Karm Yog

By Vishal Agarwal

As karm yog entails a diligent performance of actions, it is very important to discuss how kriyamāṇa karm bears no fruit in this path. First, the karm yogī identifies his svadharm (or personal duty) that is consistent with his stage in life, status in the society and his abilities etc. and performs them diligently and with faith.

He who follows any of the four different āśramas with determination, with faith and in the proper manner eventually attains mokṣa. Anugītā 20.45

Devoted each to his own duty, a person attains perfection. Gītā 18.45ab

Second, he performs his duties without desire/attachment or aversion/anger.

Passionate attachment (rāga) and aversion (dveṣa) are associated with objects of every sense organ respectively. Let none come under their sway, because these two are way-layers in his path (of karm yog). Gītā 3.34

He whose every well-undertaken action is free from desire and mental conception of its efficacy (saṃkalpa), whose karm has been burned by the fire of knowledge – him the wise call ‘learned’ (paṇḍita). Gītā 4.19

Third, he relinquishes the fruit of his actions mentally and does not crave for it.

Having relinquished attachment to the fruit of karm, ever content, without any kind of dependence, he does not perform any karm, even though he is duly engaged in activity. Gītā 4.20

It might be wondered that if he performs his duty without any attachments or desires for the fruit, then what is his motivation for performing his actions? So, fourth, he performs his actions for purifying his own ātmā and for greater good of the society.

The yogīs perform their karm with their body, with the mind, with the intellect or merely with their senses, giving up attachment, and solely for purification of their ātman. Gītā 5.11

Fifth, for himself, he acts for bare bodily sustenance and is satisfied with whatever he obtains by chance for his nourishment.

Free of all expectations (in the results of karm), with his ātmā and mind under control, having given up all desires to acquire possessions, performing bodily karm alone, he incurs no evil. Gītā 4.21

He who is contented with whatever is obtained by chance, who has gone beyond the dualities (of pleasure and pain), who is free from jealousy, who remains even minded in success and failure – even when such a person acts, he is not bound. Gītā 4.22

Sixth, he has complete control over his mind and senses, and even gives up his sense of doer-ship and regards the Bhagavān within alone as the Doer of his deeds. Such a person is really a non-doer although to others he might appear to be acting unceasingly. As he is a non-doer, his actions have no fruit –

He who is established in yog, has a completely pure ātmā, who is the master of the ātmā and who has conquered his senses, whose ātmā has become the soul of all beings – he is not tainted by karm even though he acts. Gītā 5.7

“I do not do anything,” thus one, who is established in yog, and knows the reality, should think. Whether seeing, hearing, touching, smelling, eating, walking, sleeping, breathing…Gītā 5.8

Talking, excreting (or discharging), grasping, opening and closing of eyes, he holds that it is merely the senses that are occupied with the objects of the senses. Gītā 5.9

The embodied (soul), that has renounced all karm mentally, sits happily as the ruler, within the city of nine gates, neither performing karm, nor causing karm to be done. Gītā 5.13

He whose soul is free of the egotistic condition, whose intellect is not tainted, he does not kill, nor is he bound (by his karmas). Gītā 18.17

The Bhagavān [ātmā that has mastered the mind and the senses] does not create either the agency or the actions of the world. Nor does he connect karm with the fruit. Indeed, it is one’s own nature that proceeds (works these out). Gītā 5.14

The knower of Brahman does not consider himself as the doer of his actions. Therefore, his karmas are considered neither as good deeds, nor as bad deeds. And they bear neither good fruit nor bad fruit. Mahābhārata 13.120.24

The soul which is established in yog attains steady and eternal peace upon abandoning the fruit of karm. But the soul which is not established in yog, does karm motivated by desire and is attached to the fruit, is bound. Gītā 5.12

Seventh, he offers the fruit of his karm to the Bhagavān–

Relinquishing all your karmas to Me, with your mind abiding in Me, being free from desire and egoism, with your fever (mental grief) departed, fight! Gītā 3.30

Those persons too, who full of faith and free from cavil, follow this teaching of mine at all times, they are released from the (fetters of) karmas. Gītā 3.31

Reposing (or dedicating) his karm in Brahman, having given up attachment, he is not tainted by evil just as the lotus leaf is not (wetted) by water. Gītā 5.10 [1]

Eighth, he becomes permeated with Brahman, the Divine, in all ways. He abides in Brahman, Brahman abides in him. He sees Brahman in everyone, in every object, in every act. For that reason, whatever he does takes Him to Brahman.

[For such a person] The act of offering (or the ladle) is Brahman, the oblation is Brahman, by Brahman is the oblation offered into the fire of Brahman. Brahman is indeed the goal attained by him who comprehends Brahman in his karm. Gītā 4.24

There is only one ruler, and no second ruler. He who is within the hearts of all creatures – Him alone I consider as the ruler. Just as water flows naturally whichever way the land slopes, likewise I do only those karmas that the inner ruler inspires me to do. Anugītā 11.1

Brahman alone is his sacrificial fire-sticks and fire, he originates from Brahman, Brahman is his water, Brahman is his Guru, and his mind always abides in Brahman. Anugītā 11.17

The wise see the same (ātmā) in a learned Brāhmaṇa endowed with humility, in a cow, in an elephant, and even in a dog or in an outcaste. Gītā 5.18

Ninth, as the karm yogī is completely devoted to Brahman, his actions become completely spiritualized. His work becomes his worship. Divine knowledge shines within him, destroying the fruit of his karm

The fruit of the karmas of those who have not relinquished after they die is threefold – evil, good and mixed. But for the renouncers, there is none whatever. Gītā 18.12

Winner of wealth, karmas do not bind him who has renounced his karm through yog, who has destroyed his doubts by knowledge and who is ever devoted to the ātmā. Gītā 4.41

They whose intellects are directed towards That (the Supreme Soul), whose souls are fixed on That, whose foundation is That, who regard That as the highest – they reach that state from which there is no return, with all their evils shaken off by knowledge. Gītā 5.17

He from whom the natural activities (or duties) of all beings arise and by Whom all this is pervaded, by worshipping Him through the performance of his own duty does a person attains perfection. Gītā 18.46

Therefore, our teachers say that the mode in which the karm yogī acts is ‘Nārāyaṇa Bhāva’, or a state in which every act is worship, every word spoken is a prayer, every step taken is a pilgrimage, every movement of the hand is like hands clasped in reverence to the Divine.

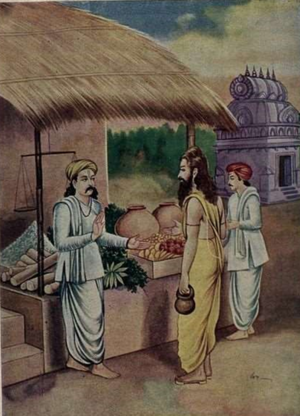

Parable: Brāhmaṇa Saṃnyāsin Jajali accepts the superiority of the Vaiśya Tulādhāra: [2]

A Brāhmaṇa ascetic Jajali spent several years studying śāstra-s and practicing meditation and other austerities. As a result, he acquired great powers of self-control. One day, a pair of birds started hovering over his head, as he stood meditating. They started constructing a nest on his head. Overcome with compassion, Jajali did not want to shake his head for the fear of scaring the birds away.

As he stood still, the birds completed the nest, and laid a few eggs in the nest! The compassionate Jajali did not want to damage the eggs and decided to stand still till the eggs hatched. When the eggs hatched and little birdlings came out, Jajali used his powers of great self-control to stand still for numerous days. Day after day, the parent birds would bring food from great distances and feed their children. In a few weeks, the tiny children grew older and mature, and flew out of the nest on Jajali’s head to live independent lives. All these weeks, Jajali kept meditating, and did not shake his neck or head lest the birds were harmed or scared in any way. His remarkable achievement and powers of self-control due to years of meditation now unfortunately gave way to a little pride. He thought, “Who else could have done this remarkable feat!”

But as soon as he had said these words to himself, a voice from the sky said, “Do not get puffed up Jajali. Your glory and greatness is not equal to that shopkeeper Tulādhāra of Vārāṇasī. And yet, even he does not say the words that you have uttered in self-praise.”

Jajali was a bit miffed. But he nevertheless proceeded to Vārāṇasī to hear what Tulādhāra had to say. When he arrived at the shop, Tulādhāra was busy weighing spices, vegetables, grains etc. for his customers. Upon seeing Jajali, he said, “I knew you were coming to see me to learn dharm.” Jajali was even more bewildered now. He asked, “How did you know that I was coming to see you? And how can you, a mere shopkeeper, teach me about dharm?” Tulādhāra replied, “Practically all the people in this world follow dharm for the sake of a selfish motive. Some want to go to heaven by performing virtuous karm. Some, like you, attain self-satisfaction and happiness by acts of compassion. You have spent all your life studying the śāstra-s and meditating. But that does not automatically lead to an understanding of dharm.”

Tulādhāra continued, “See the weighing scale that I use to weigh goods before selling them. I always weigh the goods honestly, and the beam of my scale is always perfectly horizontal. Neither do I weigh less, nor do I weigh more irrespective of whether my customer praises me or criticizes me. I stay honest not for the love of praise or fear of criticism, but because I have faith in honesty. I desire the good of all creatures, and work diligently to serve others, not for the reward of a ‘feel good’ sensation, but because I have faith in Brahman. I know that this same Brahman resides in all creatures, and therefore, I should work for the welfare of everyone, and give everyone their due. This, I believe to be the true essence of dharm – having a uniform attitude towards praise and criticism, doing good to others without any selfish motive and for the welfare of others, and having faith in Brahman.”

As Jajali spoke these words, the birds appeared from the sky and declared that although Jajali was like their father, Tulādhāra had indeed spoken the truth about the essence of dharm. Jajali now realized that one should avoid bad karm and perform good karm. But the best is to do good karm not for self-gratification (or for the fear of criticism), but for promoting good of all creatures and with faith in goodness and in Brahman. Jajali practiced this understanding of dharm, and eventually attained mokṣa.

References[edit]

- ↑ Under Gītā 3.30 and Gītā 5.10 of these verses, Śaṅkarācārya explains consistently how the message is to regard the Bhagavān as the Master, and do His work as a loyal servant, without any desire for the fruit, or sense of agency, and as if it were a Divine command.

- ↑ Source: Mahābhārata, Śānti Parva. Narrated by Bhīṣma to King Yudhiṣṭhira